Earth hovers on the brink of ecological catastrophe - actually, 20 years closer to the brink than it was at the first global climate summit, in 1992.

"Deserts continue to expand. The loss of plant and animal species has accelerated . . . . And greenhouse gases have continued to build up in the atmosphere," the Los Angeles Times explains. No matter that, 20 years ago, most nations of the world "signed off on a long list of goals and agreements" designed to ensure a different future. Nothing came of it.

And my sense is that no one expects the U.N. Conference on Sustainable Development, a.k.a. Rio+20, which begins this week, with representatives from 190 countries attending, to make any difference in our disastrous drift ever more deeply into unsustainability . . . because nothing can make a difference. We're stuck, apparently, in a system that won't be constrained by international goals and agreements, which are already compromises to that system. No matter that this is a life-devouring system that serves the interests of the very few - and at best serves them temporarily. No matter that more and more people see the insanity of this system. There seems to be no escape from it.

That is to say, there's no escape from the demands and requirements of money, the pursuit of which tramples whatever we might hold sacred, such as the future.

"These summits have failed for the same reason that the banks have failed," George Monbiot wrote recently in The Guardian/UK. "Political systems that were supposed to represent everyone now return governments of millionaires, financed by and acting on behalf of billionaires. The past 20 years have been a billionaires' banquet."

I add my voice to this frustration in order to raise a single question: What if the problem is deeper than greed, or the evil rich? Seldom does the analysis get beyond the concept of greed, whether corporate or individual. Instead, an obvious solution is advanced: Get the greedy ones out of power. And there the analysis tends to stop, because the path to doing so quickly gets incredibly vague.

Whatever the divide between the 1 percent, or the .0001 percent, and the rest of us, there's enough general prosperity in the system to implicate almost everyone in the habitual consumption of corporate products, tying our self-interest to systematic environmental destruction. Half the population is in denial that this is happening and the other half feels mostly powerless despair. And even when we think we've won the election, the victors turn out to be beholden to the same hidden interests. The system continues unabated.

What generally remains unquestioned is the nature of money itself.

In his book Sacred Economics, Charles Eisenstein points out that our notion of spirit "is that of something separate and nonworldly, that yet can miraculously intervene in material affairs, and that even animates and directs them in some mysterious way.

|

"It is hugely ironic and hugely significant," he continues, "that the one thing on the planet most closely resembling the forgoing conception of the divine is money. It is an invisible, immortal force that surrounds and steers all things, omnipotent and limitless, an 'invisible hand' that, it is said, makes the world go 'round."

Or, if it so chooses, money can decide to make the world uninhabitable. It works in mysterious ways . . .

Eisenstein's book is one of the few analyses I know of that attempts to explain money in terms larger than its own. I recommend it highly, and offer a brief synthesis of his analysis in an attempt to put Rio+20 into a context larger than "why bother?"

The destructive nature of our current monetary system, according to Eisenstein, is due to that which backs it, rendering helpless everyone who deals with money, because what backs it becomes what we are, in essence, forced to worship. If gold backs money, people worship gold. But some time ago, our monetary system evolved beyond the backing of material substances. Money, now an electronic notation on a computer screen, is backed by none other than growth itself - by the creation of more money.

"Created as interest-bearing debt, (money's) sustained value depends on the endless expansion of the realm of goods and services," Eisenstein writes. "Whatever backs money becomes sacred: accordingly, growth has occupied a sacred status for many centuries."

And this is the problem. It's not the greed of the powerful, however ferocious and consuming that might be, but the nature of money itself, our tacit and unconscious agreement on value, that has turned the system into a mechanism of unlimited growth. Thus David Korten, writing in YES! Magazine, describes the essential Rio+20 debate as "a foundational choice between two divergent paths to the human future": the Money Path or the Life Path.

This may be an impossible choice. But what if this were not the choice we needed to make? Eisenstein writes: "Today, for the first time, we have the opportunity to infuse some consciousness into our choice of money. It is time to ask ourselves what collective story we wish to enact upon this earth, and to choose a money system aligned with that story."

That is to say, what if we backed our money with something we actually valued, such as a healthy ecosystem, equitable distribution of wealth and a restored human commons?

This may be the beginning of the conversation that will save the world.

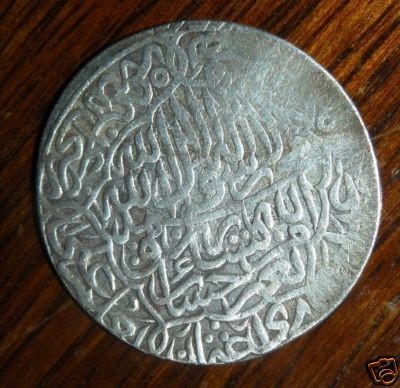

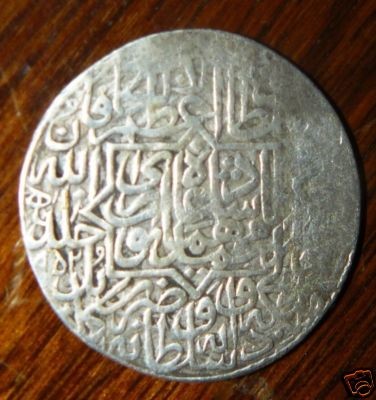

A rare Umayyad gold Dinar fetched a whooping US $4.06 million at Morton and Eden’s Oct 24, 2019 Islamic Numismatics auction. Add Buyers premiums and this coin will end up costing the buyer a tad over five million US dollars. In April 2011 this same auction house had sold another rare Umayyad Dinar for almost six million US dollars - becoming the second most expensive coin ever sold in the world.

|

| Courtesy: Morton and Eden UMAYYAD, TEMP. HISHAM (105-125h) Dinar, Ma‘din Amir al-Mu’minin bi’l-Hijaz 105h. Reverse: In field: Allah ahad Allah | al-samad lam yalid | wa lam yulad Ma‘din | Amir al-Mu‘minin | bi’l-Hijaz Weight: 4.27g References: Fahmy 128, same dies; Bernardi 48Ed; Walker ANS.16 = Miles, RIC 66. Good extremely fine, extremely rare and an historically important coin. Ex Baldwin’s Islamic Coin Auction 19, ‘Classical Rarities of Islamic Coinage,’ 25 April 2012, lot 17. The only other specimen of this coin to appear at public auction was sold in these rooms, 4 April 2011, lot 12 (for a hammer price of £3.1million). EXTREMELY RARE AND OF GREAT HISTORICAL INTEREST, dinars from the ‘Mine of the Commander of the Faithful in the Hijaz’ have the distinction of being the first Islamic coins to mention a location within the present Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. The inscription which makes this coin so special is not difficult to translate: Ma‘din Amir al-Mu’minin bi’l-Hijaz simply means ‘Mine of the Commander of the Faithful, in the Hijaz.’ But while scholars continue to study its precise meaning and significance, there are strong grounds for believing that the gold used in their manufacture came from a mine located between the Holy Cities of Makka and al-Madina, which was itself owned not only by several caliphs but which had been given to another former owner by the Prophet (PBUH) himself.

|

Islamic Numismatics is a mesmerizing world that encompasses various dynasties, spread across numerous geographical locations spanning three continents and almost 1500 years of history. People have dedicated their lives to this field. Numerous books and papers have been published on almost every type of Islamic coinage.

Numismatics is more than just a hobby. It tells historians so much about the past. The right to mint coins was one of two things that were fiercely guarded by all Muslim Monarchs – the second being the inclusion of a prayer for the monarch during Friday sermon. Islamic coins provide even more information, than coins of other cultures, as they also contain the mint name (geographical location), and the year of minting, thus providing numismatics and historians with critical information. For those unfamiliar with the Arabic language, Richard Plant’s “Arabic Coins and how to read them” will make reading Islamic coins a breeze.

Islamic coinage begun after the newly established Muslim state conquered the Sassanian empire. Umar bin Khattab, the second Khalifa asked a word or two of Islamic terminology (Bismillah) be added to the existing Sassanian coin design; thus, you see the initial Islamic coins having human portraits contained in earlier Sassanian coins. This was followed by Arabic language replacing the Pahlavi script, and the Hijri calendar replacing the Yesdigrid age. Similarly, after defeating the Byzantines, the Muslims initially started marking the existing coins Sahih or Tayyib indicating that the coins were acceptable for usage. This was followed by the removal of the horizontal bar from the cross, and addition of Islamic Terminology.

Khalifa Abd al Malik Bin Marwan was responsible for the complete redesign of the Islamic coins. The obverse of these Umayyad coins had:

لا اله الا

الله وحده

لا شرك له

There is no God except

Allah alone

He has no partner

The reverse of the Umayyad coins had:

الله احد الله

الصمد لم يلد و

لم يولد و لم يكن

له كفوا احد

Allah is the one and only God

The eternal and indivisible, who has not begotten, and

has not been begotten and never is there

an equal to Him

The margins of the coins are called ‘Bismillah,’ as it starts with Bismillah and states where the coin was minted and in what year. In Umayyad coins, the name of the Khalifa is not indicated, but, it can be deduced from the year of minting. The Byzantine emperor protested these coin reforms; however, the Khalifa dismissed the Byzantine demands.

|

| An Umayyad Gold Dinar of ‘Abd al-Malik/al-Walid I , 86h, 4.22g. From the author’s collection. |

In the centre of the obverse is the Kalima or profession of faith, while the marginal legend is /muhammad rasul Allah/ followed by Huwal Ladi Arsala Rasuluhu Bil Huda Wo deen el haqe Liyunzerahu alad deeni kullihi walo karihal mushrikoon [He is the One who sent His messenger with guidance and true religion to prevail over all other religions even if the polytheist dislike it](Qur'an 9:33)

In the centre of the reverse is the Surat al-Ikhlas (Qur'an 112:1-3), and in the marginal legend is the date.

The Abbasids made slight changes to the Umayyad formula, by adding the Khalifa’s name to the coins.

|

| Heavy Gold Dinar of last Abbasid Khalifa, al-Musta‘sim (640-656h), Madinat al-Salam 642h, 10.42g (SICA 4:1309-1311; A 275). From the author’s collection. |

Obverse : In seven lines; Al-Imam/ La Ilaha Illa Allah/ Wahdahu La Sharuka Lahu / Al-Musta'sim Billah/ Amir Al-Mu'menin/ Bi Nasr Ellah/ to the right vertically : Lillah Al 'Amr min kabl Wa Min Ba'ad, To the left vertically : Wa Yauma Izin Yafrahu 'al Mu'emenun. [The Imam/ No God but Allah/The one without partners/Al-Musta’sim Bbillah/ the leader of the believers. The matter before and after is to Allah in that day the believers will be Joyful by the victory from Allah]Qur’an. All in a flower shaped frame forming the outer MARGIN : Bismillah Duriba Haza Al Dinar Bi Madinat Al-Salam Sanat Ithnatayn Wa Arba'in Wa Suttuma'at. [The Imam/ No God but Allah/The one without partners/Al-Musta’sim Bbillah/ the leader of the believers.

Reverse: In five lines : Al-Hamdu Lillah/ Muhammad/ Rasulu Allah/ Salla Allah Alayhi/ Wa Sallam, Vertically to the right : Walaw Kariha/ and vertically to the left : Al-Mushrekun. MARGIN : Muhammad Rasul Allah Arsalahu Bil Huda Wa Din Al Hakk Lyuzhirahu 'Ala Al-Dina Kulahu.

Reverse Center:

الحمد لله

محمد

رسول الله

صلى عليه الله

و سلم

Sides:

ولو كره

المشركون

Margin:

محمد رسو ل الله ارسله ه بالهدى و دين الحق ليظهره على الدين كله ولو كره المشركون

The Ottoman Coins used the Usmani script.

|

| An Ottoman gold Sultani, of Suleyman I, AH 926 (1520), Sidrekapsi Mint, Mint name in one line. The date is given at the bottom. From the author’s collection. |

Quality coins from Islamic Spain are also in considerable demand.

|

| A Murabitid (Spain) gold Dinar, ND, Ali B. Yusuf, AH 500-537; A-466. From the author’s collection. |

Sultan Baybar’s coins carry his ‘lion,’ emblem.

|

| Mamluk, gold Dinar of Sultan Baybar I (AH 658-676) ( 1260-1277), A-880, has a slight Uneven Strike, but is in an almost Uncirculated condition. From the author’s collection. |

The Indian Islamic coinage quickly switched to the Indian monetary weight system of heavier mohurs, instead of the standard dinars used in other parts of the Islamic world. The dinar had followed the Roman monetary system of denarius. Some of the initial Indian Islamic coins were bilingual.

Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni’s following silver dirham has the obverse in Arabic, and the reverse in Sanskrit.

|

| Silver dirham of Mahmud (998-1030), bilingual type, Mahmudpur (Lahore), 2.81 gm., Diameter: 19 mm., Die axis: 7 o'clock, Arabic legend: Shahada followed by yamin al-daula wa amin mahmud al-milla (Mahmud guardian of the faith), al-qadir above, billah at left; Date in the margin: AH 418 (= 1027-1028 CE) / Sanskrit legend in Sharada letters: avyaktameka muhammada avatar nripati mahamuda (the Invisible is One, Muhammad is the manifestation, Mahmud the king). Courtesy: CoinIndia Gallery |

|

| Gold Dinar of Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni, 24 mm, 3.72 gms, 388-421 AH, (998-1030). From the author’s collection. |

|

| Silver Tanka of Sultan Iltutmish, Delhi, India, AH 607-633 (AD 1210-1235), 26mm, 10.68 gm, 3h. Citing Khalifa al-Mustansir. CIS D38. Obverse: ruler’s titles: al-Sultan al mu’azzam, ending with nasir amir al muminin. Reverse: Shahada, and Amirul Momineen al-Mustansir billah. R 835; NW 50E. From the author’s collection. |

|

| Gold Tanka of Sultan ‘Ala al-din Muhammad (695-715h), Dar al-Islam, Delhi, India, date off flan, 11.00g (G&G D220). Obverse: ruler’s titles: al-sultan al-azam Ala al-dunya wal din abul muzaffar Muhammad shah al Sultan. Reverse: Sikandar al thani legend, with mint date in the margin, R998, NW. From the author’s collection. |

|

| Gold Tanka of Sultan Muhammad III bin Tughluq, AH 725-752 (1325-51), Fr-459. Hadrat Delhi, India, GG: D 331, 12.8 gram, al-watiq type. Rare. Obverse: Al-wathiq bi-ta yid al-rahman Muhammad shah al-sultan (he who trusts in the support of the Merciful; Muhammad Shah al sultan). Mint and date in margin. Reverse: Ash Shadual Lailaha wo ashShaduan Mohammad abduhuhu wo rasuluhu (I testify that there is no God but Allah and I testify that Mohammed is His servant and His Messenger. From the author’s collection. |

|

| Gold Tanka of Sultan Muhammad III bin Tughluq, AH 725-752 (1325-51), Fr-459. Dar al Islam, Delhi, India GG: D341, Rare, 11 grams, al-mujahid type, R1203; NW 479. Obverse: Al-mujhid fi sabil Allah Muhammad Bin Tughluq Shah (the Mujahid in the path of Allah Muhammad Bin Tughluq Shah). The names of the first four caliphs around. Reverse: Shahadah, with mint and date in margin. From the author’s collection. |

|

|

| Silver Shahrukhi of Babur, 1525-1530, Lahore Mint, Mughal Empire

Kalima in three lines across field; all within ornate circular frame; titles in outer margin / Name and titles of Babur in three bands across field, each separated by a knotted borderline - the name and titls are given as Zahir al Ad-din Muhammad Babur Bashah Ghazi; mint formula to lower left, date (936 AH = 1529 AD). Lahore mint. 23mm, 4.65 grams. Whitehead (Punjab) 12. From the Author’s Collection. |

|

| Mughal, Silver Shahrukhi of Mohammed Humayun

Obverse: Mohammed Humayun Badshah Ghazi…. Reverse: Shahadah, Names of the four Rashidun Khalifas. From the author’s collection |

|

| Mughal, Silver Rupee of Jahangir, Kashmir mint, AH 1024, year 10 KM 145.10. Obverse: Jahangir Shah Akbar Shah |

|

| Mughal, Gold Mohur of Muhammad Shah Jahan, AH 1037-68 (1628-58), Fr-787; KM-255.6 Obverse: Sahib e Qiran Mohammed Shihabuddin Shah Jahan Badshah Ghazi. Reverse: Shahadah, Mint name (Surat), and date. From the author’s collection. |

|

| Mughal, Gold Mohur of Aurangzeb, AH 1068-1118 (AD 1658-1707), 10.97 gr, Ahsanabad, year 47. Obverse: Aurangzeb Alamgir; zo go mehar…. Reverse: Maimanat Manoos; Mint and date. From the author’s collection. |

|

| Durranis, Gold Mohur of Ahmad Shah, AH 1160-1186; (1747-1772 A.D.), Shahjahanabad, AH 1173, year 14. AV 10.85 g. KM 765. From the author’s collection. |

|

| Hyderabad, Gold Ashrafi of Mir Osman Ali Khan Asaf Jah VII, 1911-1967. AH 1341, RY 12 (1918 A.D.). AV 11.20 g. Obverse: Char Minar gateway, with the letter ‘Aen’ inside the arch, date is below, right margin: ‘Nizam ul Mulk,’ Top margin: ‘Asaf Jah,’ left margin: ‘Bahadur’. Rev. Calligraphic legend with regnal date, ‘Aik (one) Ashrafi,’ in the center. KM 44. Mint state. From the author’s collection. |

The value of a coin depends on several factors. It’s condition – fine, very fine, extremely fine, choice, etc.; its mint – where it was minted; its Rarity or lack thereof. Above all it’s demand. For example a very ancient, rare coin, from a desirable mint may not have much demand, and hence may not fetch much. Whereas, coins that have high demand, say a Chengiz Khan’s coin, even in poor condition may fetch a decent amount. That being said, rare, precious coins are handled with extreme care, as the slightest blemish could dramatically reduce the price of an extremely valuable coin. While inexpensive, common coins are available by the bucket load, valuable coins are difficult to come by, and when they do appear on the market, collectors try to outbid each other for it. Trolling the local coin shows is a good way to get started. There are numerous large, reputable auction houses that maintain extensive databases to research coins of all cultures. There are Islamic email groups that can be of help too. Museums are good places to view rare, valuable coins.

Misbahuddin Mirza, M.S., P.E., a licensed Professional Engineer, registered in the States of New York, and New Jersey, served as the Regional Quality Control Engineer for the New York State Department of Transportation’s New York City area. He has written for major US, and Indian publications. He is an avid student of history, Islamic numismatics, and comparative religious studies.