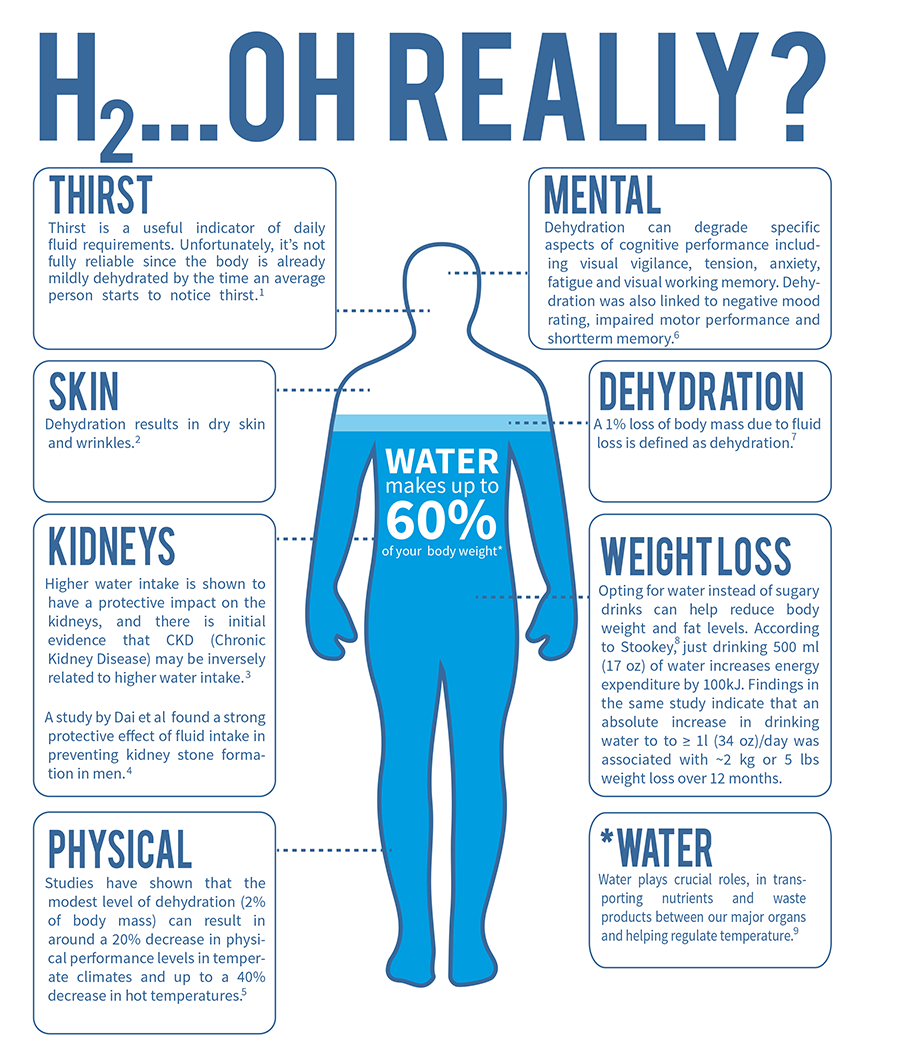

“We Made from Water Every Living Thing” (Infograph)

Islam gives a unique importance to water. The Holy Qur’an describes it as a life-giving, sustaining, and purifying natural resource. It is clearly viewed in Islam as the origin of all life on Earth, the substance from which God created man (Surat: Al-Furqan: 25:54).

The Qur’an emphasizes its centrality: “We made from water every living thing” (Surat Al-Anbya’: 21:30). Water is the primary element that existed even before the heavens and the earth did: “And it is He who created the heavens and the earth in six days, and his Throne was upon water.” (Surat Hud: 11:7).

The water of rain, rivers, and fountains runs through the pages of the Qur’an to symbolize God’s benevolence: “He sends down saving rain for them when they have lost all hope and spreads abroad His mercy.” (Surat: Al-Furqan: 25:48).

Scientists found that water is incomparably the best liquid option for staying hydrated and healthy. Plants and animals are mostly water inside, and must drink water to live.

In fact, it gives a medium for chemical reactions to take place, and is the main part of blood. It keeps the body temperature the same by sweating from the skin.

Additionally, water helps blood carry nutrients from the stomach to all parts of the body to keep the body alive. Water also helps the blood carry oxygen from the lungs to the body.

Moreover, saliva, which helps animals and people digest food, is mostly water. Water helps make urine. Urine helps remove bad chemicals from the body. The human body is between 60% and 70% water.

Other drinks and foods can help you stay hydrated, but some may add extra calories from sugar to your diet. Drinks like fruit and vegetable juices, milk, and herbal teas can contribute to the amount of water you get each day.

Infographic

Islamic Roots of Modern Pharmacology

Around the 8th century, one man took it upon himself to dig deeper into this amazing world of chemistry. A long forgotten historical figure, Khaled Ibn Yazeed came from the house of the Umayyad Caliphate. It was very unusual for a man in his social and economical stature to adopt such an unrecognized profession. However, his decision was a turning point in the history of chemistry.

Ibn Yazeed started his journey by translating Greek and Roman references in the field. He studied chemical reactions and started his pioneering experimentations in synthesizing drugs and remedies.

Just as the Greeks and Romans had acquired their learning from ancient Egyptian and Sumerian breakthroughs, Ibn Yazeed set the foundation upon which chemistry and pharmacy could be studied which was later built upon by his successor Jabir Ibn Hayyan.

By the beginning of the 9th century, pharmacy was already a well established, independent profession with well regulated rules and laws.

In fact, pharmacists were knowledgeable about drug use, compounding, preparation, and dispensing. At that time, pharmacists mastered dosage adjustment, drug interaction, and prevention of drug adulteration.

Interestingly, Muslim physicians have further developed the field of pharmacy. Being the most knowledgeable about body ailments and diseases, physicians were the most suited to develop and prescribe the cure.

Famous physicians like Al-Razi, Ibn Sina and Al-Kindi, contributed much in the advancement of this field of science. Furthermore, they combined their knowledge about medicine with herbal remedies, chemistry, and philosophy to develop an amazing body of work describing disease diagnosis, description of appropriate remedies, and the required dosages.

Al-Biruni’s book, ‘The Book of Pharmacology,’ Al-Zahrawy’s 30 volumes ‘Al-Tasrif’ (Dispensing), Al-Razi’s ‘Al-Hawi’ (The Comprehensive Book on Medicine), ‘The Secret in Chemistry’, Al-Mansur Muwaffaq’s ‘The Foundations of the True Properties of Remedies’ and Ibn al-Wafid’s work ‘The Book of Simple Drugs,’ were some of many outstanding references in pharmacology at the time.

Al-Biruni’s book, ‘The Book of Pharmacology,’ Al-Zahrawy’s 30 volumes ‘Al-Tasrif’ (Dispensing), Al-Razi’s ‘Al-Hawi’ (The Comprehensive Book on Medicine), ‘The Secret in Chemistry’, Al-Mansur Muwaffaq’s ‘The Foundations of the True Properties of Remedies’ and Ibn al-Wafid’s work ‘The Book of Simple Drugs,’ were some of many outstanding references in pharmacology at the time.

As a result, upon the work of these great Muslim scientists, the modern Western World has founded its pharmaceutical knowledge.

The most important aspect of Muslims’ development to the pharmaceutical profession, though, was their honoring of the Islamic teachings.

They believed in the Hadeeth that states, “God created the disease and the cure, and made a cure for every ailment; so seek healing but do not seek treatment with haram (unlawful means.)” (Abu-Dawood and al-Bayhaqi).

Consequently, Muslim pharmacists and physicians didn’t delve into any unlawful treatments or quackery. They based their knowledge and studies on scientific experimentations and practical experiences. Additionally, they honored the whole human being, body and soul, and sincerely and ethically pursued their mission in easing people’s pain and relieving their sufferings.

Physicians, like Al-Razi, advocated resorting to diet and herbs for treatment before referring to chemical drugs. His one-of-a-kind book, ‘Tibb Al-Fuqara’a’ (Medicine of the Poor), described ways of treating diseases using affordable foods and herbs rather than expensive preparations and formulations.

While delving into this great history, I can’t help but feel awed by such wisdom, knowledge and honor. And, I can’t also help but wonder when the achievements of modern-day Muslims will match that great era of human advancement.

We first published this article in 2009 and we currently republished it for its importance.

References:

As-Sergany, R.. Khaled Ibn Yazeed. Retrieved from: www.islamstory.com. 2008.

As-Sergany, R.. العلم وبناء الأمم [Science and the building of nations]. Egypt: Iqraa. 2007.

Al-Hassani, S. (Editor). 1001 Inventions: Muslim Heritage in Our World. UK: Foundation for Science Technology and civilization. 2006.

National Library of Medicine. Islamic Culture and the Medical Arts: Prophetic medicine. April 5, 1998. Retrieved June 6, 2007.

Rhazes: Persian Muslim Galen

Abu Bakr Mohammed ibn Zakariya ar-Razi (born in Rey, Iran – c. 841-926) gave no early indication that he would someday be considered the greatest of all Islamic Caliphate’s physicians.

He spent his youth pursuing music, mathematics and alchemy. As an alchemist he pioneered in the use of mercurial ointments in the treatment of disease. Then, at the age of forty, he turned his attention to medicine.

Ar-Razi (later known in the West by the Latinized version of his name, “Rhazes”) went to the great teaching hospitals of Baghdad, the Abassid capital, for his training. Completing his studies, he returned to Rey and assumed directorship of its hospital.

His reputation grew rapidly and within a few years he became the director of a new hospital in Baghdad. He approached the question of where to put the new facility by hanging pieces of meat in various sections of the city. Several days later he returned and ordered the hospital built at the site where the meat showed the least amount of decay.

Ar-Razi is one of the greatest Muslim clinicians and its most original thinker. A prolific writer, he turned out some 237 books, about half of which deal with medicine. His treatise, “The Diseases of Children,” has led some historians to regard him as the “Father of Pediatrics”. Ar-Razi was the first to identify hay fever and its cause. His work on kidney stones is still considered a classic.

In addition, he was instrumental in the introduction of mercurial ointments to medical practice. Ar-Razi was a strong proponent of experimental medicine and the beneficial uses of medicinal plants and drugs.

A leader in the fight against quacks and charlatans, he called for high professional standards for practitioners. He also insisted on “continuing education” for already licensed physicians.

Following his term as hospital director in Baghdad, he returned to Rey where he taught the healing arts in the local hospital, and continued to write. Moreover, his first major work was the ten-part treatise “Al-Kittab al Mansuri.”

Abu Bakr Muhammad ibn Zakariyya Al-Razi, was a Persian polymath, physician, alchemist and chemist, philosopher and important figure in the history of medicine.

In it, he discussed such varied subjects as general medical theories and definitions; diet and drugs, and their effects on the human body; maternal health and childcare; skin disease; mouth hygiene; climatology and the effect of the environment on health; epidemiology; and toxicology.

Revolutionary Polymath

Ar-Razi also prepared “Al-Judari wal Hasbah” the first treatise ever written on smallpox and measles. In a masterful demonstration of clinical observation and acumen, Ar-Razi became the first to distinguish the two diseases from each other. At the same time, he provided still valid guidelines for the sound and rational treatment of both diseases.

Ar-Razi’s greatest work was a medical encyclopedia of twenty-five books, Al-Kittab al Hawi. He spent a lifetime collecting data for the book. It’s a summary of all the medical knowledge of Rhazes’s time. Yet, he also augmented it by his own experiences and observations.

In “Al Hawi,” ar-Razi went beyond the simple translations of his predecessors. He also emphasized the need for physicians to pay careful attention to what the patient’s history told them, and not merely accept the obvious answer.

In a section entitled, “Illustrative Accounts of Patients,” ar-Razi demonstrated this tenet. One patient, living in a malarial district and suffering from intermittent chills and fever had been diagnosed with malaria that seemed to be incurable.

When ar-Razi was examining the man, he refused to accept the obvious answer to illness and did a thorough examination. Seeing pus in the patient’s urine, ar-Razi made the correct diagnosis of an infected kidney and treated the patient successfully with diuretics.

The importance of ar-Razi’s work to later physicians cannot be overestimated. “Al-Kittab al Hawi” was translated in Latin (as “Liber Continens”) and became one of the standard medical reference works of Renaissance Europe. In fact, portions of it were still in use in European medical schools until well into the 19th Century.